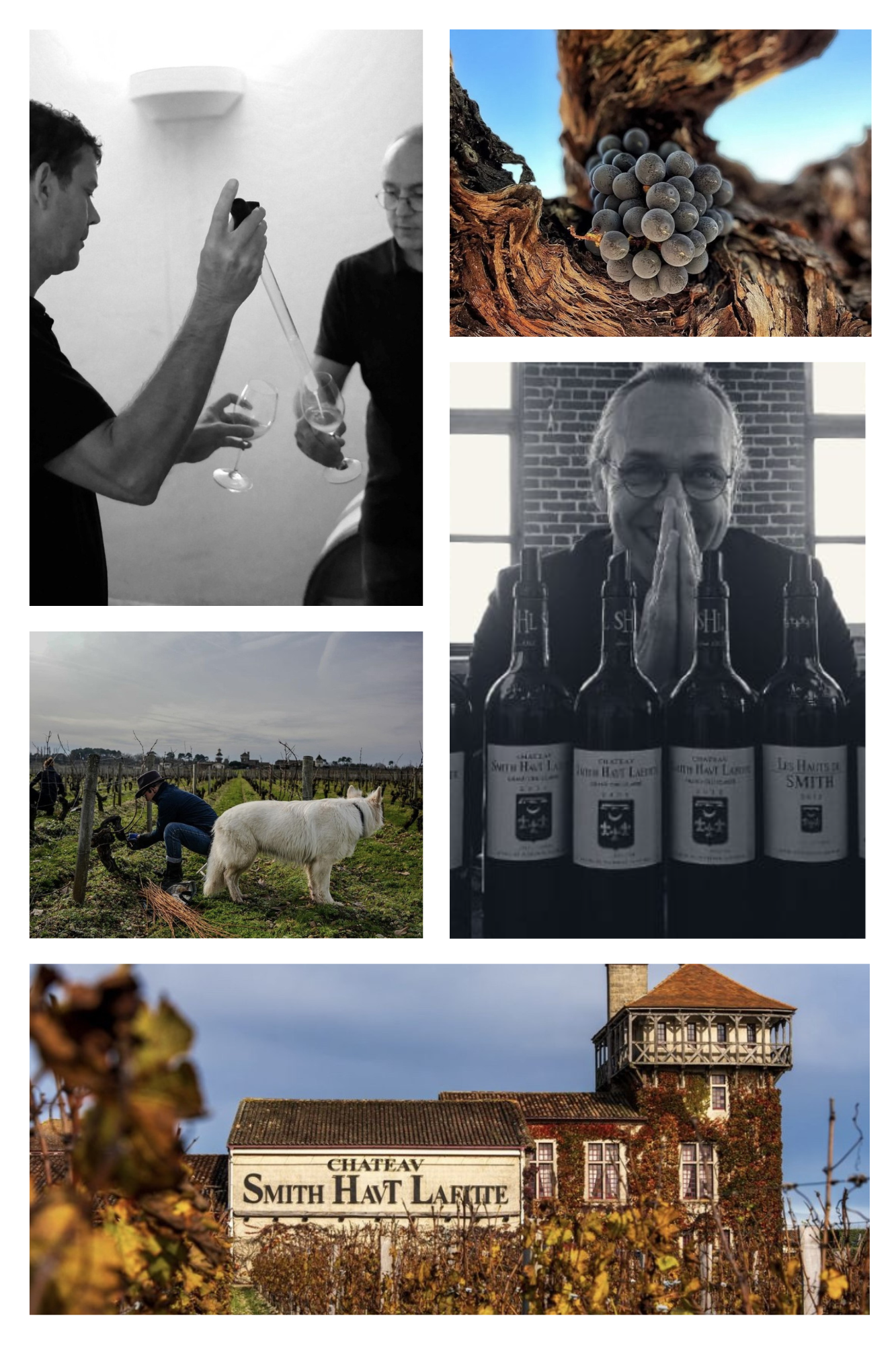

Fabien Teitgen

Managing director, agronomist and oenologist

Château Smith Haut Lafitte

Grand Cru Classé, Pessac Leognan

Gerda Beziade: Can you tell about us?

Fabien Teitgen: My background is fairly straightforward. I’m originally from Lorraine, an industrial region, but part of my family worked in agriculture. In particular, my great-grandfather owned vines and fruit trees. He was a distiller. I often spent time with him, savouring the little drop of mirabelle plum that fell from the still. This made me want to work in agriculture or forestry, especially as my father had always worked in the forestry sector. So I quickly decided to go into agronomy. During my studies, I met people who specialised in viticulture and oenology, and I discovered that it was possible to learn how to make wine, whereas initially wine seemed inaccessible to me. I began to take an interest in its culture, because wine is the result of a very specific production, a long process that starts with the land and ends with a transformed product, ready to be consumed and shared. Wine production provides a direct link with a finished product, which is extremely important to me. I love this relationship between the plant and the glass. I did my end-of-studies work placement in Bordeaux, at Canon La Gaffelière. I joined Smith Haut Lafitte in October 1995 as vineyard manager for 6 years, then as technical director. Today, I’m also Managing Director. I’ve followed all the developments at this estate: the purchase of Château du Thil, the involvement in Château Beauregard and Château Saint Robert as well as in Sauternes, and more recently, overseeing the acquisition of Cathiard Vineyard in the Napa Valley.

GB: What are the personal challenges you face in your job?

FT: The real challenge today, and even more so tomorrow, is viticulture. Without good grapes, we can’t produce good wines. My daily challenge is always to go into the details. To get a good result, it’s crucial to pay attention to them every day. Maintaining a constructive atmosphere around the realisation of the details by the whole team is essential. I wake up every day with the aim of producing a fine wine, and of doing even better tomorrow. This improvement will happen if we pay attention to detail. Another challenge is to find people who want to work in the vineyards, because these days there’s unfortunately a lack of interest in agriculture. It’s a shame, because it’s a fantastic profession. Producing a better wine is not simply a matter of adding more and more. It’s about working on harmony, elegance and the overall integration of a whole. It’s a horizontal progression. I work for the owners, Florence and Daniel Cathiard, who have a lot of ideas and energy. It’s stimulating to work with them and for them, because they allow us to achieve many things, like this beautiful project in Napa. We’re not limited by tradition or rules, as long as we adopt a positive and qualitative approach. As soon as we or they have an intuition, we put it into practice and launch the idea. We are committed to a dynamic of evolution, constant questioning and the search for progress: this encourages creativity and progress. This curiosity on the part of Florence and Daniel is a real driving force behind the progress of our properties.

VINE GROWING

GB: How do you feel about climate change?

FT: Cautiously, but always positively. The weather changes and evolves, so you have to know how to adapt. At the same time, a year like 2022, marked by drought and heatwave, shows that vines, which are well cultivated in Bordeaux, are very resilient. This reassures me about the impact of the heatwave, which used to be a source of concern. We need to adapt, but we still have some time to do so. We have a few ideas: adapting rootstocks, grape varieties, pruning methods and vine management. For years, we’ve been trying to capture the light to improve the ripening of our grapes. Perhaps tomorrow, as we’re doing in Napa, we’ll have to look for shade to protect the grapes and delay ripening. There are ways of doing this and we need to look at countries that are warmer than ours. Another essential point for me is the relationship between the vine and the soil, and the life between the two. If we manage to have vines with deep roots that explore and are in balance with the soil, the soil can help the vines to cope with the stress of heat and drought. We saw this in 2022! These are the approaches that nature has shown us in this vintage and which we need to focus on to adapt the vine and its culture to Bordeaux.

GB: You have a solid 30 years’ experience here at Smith Haut Lafitte. What are the biggest changes since your arrival?

FT: Climate change, of course, but also the evolution of our objectives. Today, our aim is to produce wines that are more precise and that reflect the terroir. Our standards are much higher than they were 30 years ago. This is radically changing the way we work and forcing us to take a much sharper look at viticulture. We no longer have a single set of specifications for the vineyard, but adapt to each plot and even to each zone within the same plot. We need to understand what the plant and its soil need. By using our knowledge of this relationship and optimising it, we can obtain grapes of great quality and very distinctive characteristics. We need to adapt to the way the vine behaves in relation to its soil.

GB: You work your white plots with horses. Why only white plots and what impact do they have on the soil?

FT: This approach was originally a pragmatic decision. The slopes of the whites here are made up of the grave clayey wine. We have springs, in particular those called Les Sources de Caudalie. The soil is relatively wet and therefore extremely sensitive to ‘compaction’. ‘compaction’. We started using horses to work the soil in 1998! We quickly realised that the soil is much less compacted by the horse than by a tractor, which is heavier. What’s more, the horse doesn’t always put its foot down in the same place. We don’t use horses exclusively for all the work, such as pruning the vine, for example. It’s a practice that simply allows us to limit the number of tractors we use, and it has regenerated the soil in a very interesting way. Thanks to cultivation with horses and grass cover, we no longer have any erosion in these plots and the soil structure is much better than before. We haven’t extended the use of horses everywhere, because it’s not necessary for soils that aren’t very sensitive to compaction; above all, I want to remain pragmatic.

GB: SHL has been certified organic since 2019. Why did you make this choice?

FT: Organic farming focuses on the relationship between the plant and its soil. It’s a living ecosystem that needs to be managed. As far as fertilisation is concerned, we don’t feed the vines directly. We add compost to the soil and all the living organisms in the soil feed the vines. Organic farming greatly encourages soil life.

GB: This method of viticulture is coming under increasing criticism because of the use of copper…

FT: Yes, and we have considerably reduced its use compared with our grandfathers. They used to work with one treatment. Now we do treatments all year round. Copper is a heavy metal that doesn’t degrade, and you shouldn’t use a lot of it because it can poison the soil. The level we use today, even in a wet year like 2023, is not a cause for concern, and we keep a close eye on our soils. Our aim is to keep the soil alive and rich in humus, to leave a legacy for the next generation.

GB: How do you quantify the living character of your soils?

FT: That’s an excellent question. I don’t use a quantitative method for that. It’s more a qualitative perception based on what’s growing. Certain plants indicate when there’s a problem. What’s more, during ploughing, we can get an idea of the state of the soil. We plough as little as possible because maintaining grass cover is a more effective method of aerating the soil, as is often the case in nature. We have to try to work with nature and get the benefits we need from it. I prefer to let plants grow spontaneously rather than sowing, so that I can understand the soil better. When there is a wide variety of plants and earthworms, we know that the soil is alive. That’s common sense, and for me it’s more important than laboratory analysis.

GB: In 1982, 1990 and even more recently in 2009 and 2010, the châteaux were producing good yields and exceptional wines. Lately, the predominant feeling is that this is no longer possible. To produce exceptional wines, are estates doomed to produce small quantities?

FT: I don’t see it that way, because I’m an eternal optimist when it comes to nature and what it can offer us. Exceptional wines are a gift from nature. As far as I’m concerned, it’s entirely possible that one day all the planets will align perfectly and that there will be no climatic problems, allowing us to produce a great vintage with good quality and good yields. What we’re seeing with climatic events is that there are more accidents than before, such as frost, heavy rain in May and June, drought and even hail. This affects quantity, but not necessarily quality. Even under these conditions, we manage to produce high-quality wines that are highly representative of their terroir. Admittedly, in economic terms, these are more difficult vintages. But I’m not a fatalist. Times change, things evolve, and these changes won’t always be a problem.

The Technical Revolution

GB: You mentioned SHL’s identity, has it changed over the last 30 years?

FT: No, its identity hasn’t changed. We’ve simply expressed it differently and more fully. All the work we’ve done in the vineyard has helped to accentuate the typical character of our grapes. SHL’s identity is expressed in the red wine by an aromatic complexity closely linked to the gravelly soil, particularly smoke. It is an empyreumatic character (this word characterises a large family of burnt aromas such as tobacco, smoke, roasting, caramel, toast, pepper, etc.). We mustn’t forget that our terroir is 30% clay-limestone, which gives the wine a fresher, more powerful and structured feel, an important characteristic of today’s SHL. Our wines have great density, with lovely velvety textures thanks to the exceptional ripeness of our Cabernet Sauvignon on the gravelly soils. As for our whites, they represent an almost impossible combination to reproduce. They are rich and powerful, yet crystalline, saline and extremely delicate. This is really the hallmark of SHL, where the Sauvignon Blancs are planted on clay gravel.

GB: Since Florence and Daniel bought the estate, a great deal of investment has been made to improve the quality of the wines. Where is there still room for improvement?

FT: Progress is not a vertical race, but rather an evolution of adaptation. You have to adapt to the times, to a viticulture that is constantly evolving. Technology is only a tool. The quality of the wine is determined as soon as the pruning shears are cut. Technically, there are sometimes advances made by machines that can improve quality. But there are also technical advances that can produce better wines. The major step forward was the introduction of optical sorting, which eliminated all the small plant defects in the harvest. The latest advance, which is not yet complete, concerns de-stemming. Incorrect destemming can damage the grapes, spoil the harvest and denature the fruit. If destemming fully preserves the bunch and the berry, it opens up impressive possibilities for red wines. Today, progress is made in many details. I no longer believe in a revolution, but in an evolution of details. Sometimes the less you do, the better. At SHL, we also produce white wine, and this activity helps us to make progress in the production of red wine, because to make white wine, extreme technical rigour is necessary.

GB: You are also responsible for Cathiard Vineyard in California, which you bought in January 2020. As a renowned technician, what experience does this bring to you?

FT: The takeover meant that we had to make a reset. We went to a different part of the world, even though the grape varieties are identical. There’s a majority of Cabernet Sauvignon, so we have to ask ourselves: ‘How do we grow vines here?‘

The rootstocks and spacing are not the same, and the bunches are shaded. You have to question yourself. For me, that’s been the strongest part of my experience since I took over. I’m having a great time asking myself all these questions. When I arrived, we said to ourselves ‘we’re not going to make an SHL in California. We’re going to make a Californian wine with our Bordeaux sensibility”. We replanted plots, but not at 10,000 vines per hectare, as is the case here. We planted them in the American style (lower density and open canopy). We went there to discover a new place, to find good ways of growing vines, to find a link with the soil and to express a new identity. Having two properties in such different places helps me to make decisions in both directions.

In 2022, when I came back from Napa, with the heatwave in Bordeaux, I asked myself, ‘What are we doing there?’ So we stopped trimming, leaf removal and working the soil, and protected the bunches. In the future, we’re going to take a lot of inspiration from Napa for our viticulture so that we can develop our vines here.

Harvest 2023

GB: Could you describe 2023 in a few words?

FT: Balanced with texture.

GB: Can you say a few words about the 2023 harvest?

FT: The harvest wasn’t too complicated and was actually quite serene. The bad memories go back to May and June. Those were months marked by numerous battles to manage mildew. There wasn’t much rain during the harvest and we started picking the white grapes on 25 August. The conditions were warmer than usual, so we opted for an early harvest, but that didn’t cause us any problems as we’re used to doing it. Despite a reduced harvest due to mildew, in the end we managed the situation well, especially as there was no rain and no rot. Unfortunately, the yield was low. The last good vintage in terms of quantity was in 2019. To sum up, we weren’t too badly affected by the frost, but rather by mildew and small berries linked to water stress in September.

The Wine

GB: Could you name a favourite bottle here at SHL?

FT: It’s a 2016. I love this vintage. This wine has everything for me. It’s very representative of SHL, with the distinctive Bordeaux signature of elegance and freshness, yet ripe and dense. It has a wonderful texture and superb complexity. You can drink it now and enjoy it, and it will be just as delicious in 10 years’ time. It’s like a timeless vintage, an immediate pleasure. We really enjoyed making it. It really is a great Bordeaux vintage.

GB: Which of SHL’s trilogy of 2018, 2019 and 2020 do you prefer?

FT: Each vintage has its own particularity: the 2018 has more substance, it’s tighter. The 2019 is the vintage of total elegance, with a very seductive side. Nevertheless, the 2020 is the most complete of these 3 vintages. It combines the qualities of these two vintages. It has more structure and smoothness than the 2019, as well as superb balance. The 2020 vintage is really beautiful. GB: Is there a vintage that the market has underestimated? FT: There are several, but one of the latest is the 2011 vintage. This is often the case after great vintages like 2001 and 2006. These are vintages that are neglected, because everyone focuses on the great vintages that precede them. Although a little less good in comparison, this vintage is truly excellent. In the shadow of its predecessors, it goes unnoticed, but a few years later, you realise that it’s exceptional.

GB: Is it the same for 2017 and 2021?

FT: As far as 2017 is concerned, it is very much appreciated here at SHL. It seems to me that it is less in the shadows. As for 2021, that’s different. It is well perceived by the market and the press, contrary to what we might have feared for this ultimately atypical vintage. During the harvest in 2021, I had the impression that I was reliving the atmosphere of 1996. Some of my young colleagues were panicking at the thought that there were still grapes to be harvested and that it was raining. They didn’t know what to do because it hadn’t rained during the harvest since 2015. This is something I’ve experienced for years, from 1995 to 2005. It rained during the harvest and we had to take risks.

Gerda BEZIADE has an incredible passion for wine, and possesses a perfect knowledge of Bordeaux acquired within prestigious wine merchants for 25 years. Gerda joins Roland Coiffe & Associés in order to bring you, through “Inside La PLACE” more information about the estate we sell.