Jean-Jacques Dubourdieu

General Manager of Domaines Denis Dubourdieu

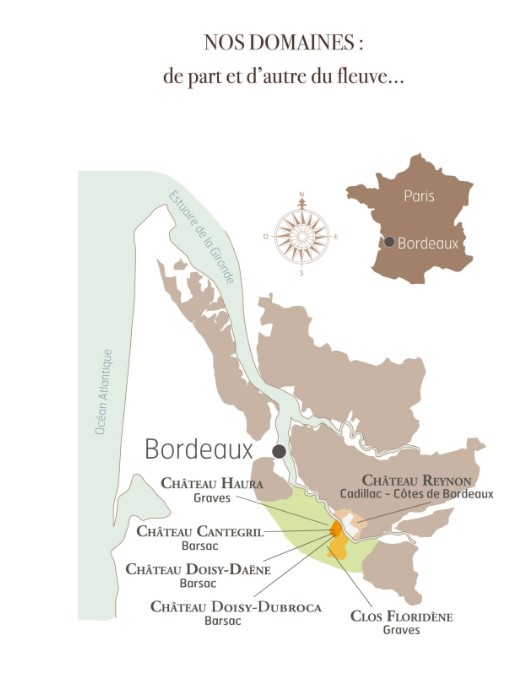

Châteaux Doisy Daene, Clos Floridène, Doisy Dubroa

Reynon, Haura, Cantegril

Gerda: What are the main challenges you personally face in your profession?

Jean-Jacques: My main challenge is to showcase our efforts in doing everything possible to make the best wine, and to ensure the market accepts the price we believe is fair. That’s the main difficulty of my job. Fortunately, we have strong brands for some of our wines, and we succeed in this effort. But for lesser-known properties and appellations, it’s a big challenge. In Sauternes, the challenge is even greater because our process is more expensive than elsewhere, and the sale price does not sufficiently reflect the efforts, sacrifices, and risks taken each year.

Ten years ago, production costs were lower. Today, producing good wine is a real economic challenge, especially if we don’t sell a bottle for €100. We must comply with a series of standards that complicate our production. All our properties have been RSE certified since July 2023. It’s exciting, and we hope we can eventually see the rewards of our efforts.

We’ve been recognized for our quality for four generations, but the challenge is to build on this quality. Our challenges are both short and medium-term: keeping the business alive in the short term and passing it on in the medium term. If we don’t make our efforts profitable, it will be hard to pass the business on, which takes a lot of meaning out of what we do.

I’m 43 years old, and when I plant vines, it’s a not for me but for the 5th generation. This year, we are celebrating the 100th anniversary of Doisy-Daëne, and my children or niece will continue if we manage to make our efforts worthwhile. We’ve made it this far, but in recent years we’ve faced Covid, frost on our estates, the global geopolitical situation, and the disrupted operations of La Place, our main partner. Teams have changed, and the priorities of my partners have shifted. Tomorrow’s world will inevitably be different. We produce good quality wines for distribution, but they are not the most profitable for La Place de Bordeaux.

How do we remain a priority for commercial partners for whom our wines are not the most interesting ? That’s another aspect of value creation, because it’s also linked to a motivated sales team working with our wines. Today, we’re wondering whether La Place can still play a role for us. La Place focuses on 30 labels that are known worldwide. How can we ensure that our wines, unbeatable on the international stage, are still distributed, visible, and valued? It’s a real challenge.

Harvest 2023

G: Could you share a memory of the 2023 harvest?

JJ: We are very happy with the quality of the 2023 vintage because it reflects many of the investments we’ve made in the vineyard over the past 10 years. 2023 is a promising vintage in terms of volume. Some had a very comfortable harvest, while others didn’t produce much at all. We are among those who had a comfortable yield. The 2023 vintage was less affected by water stress compared to 2022; the year was more peaceful, except for an excessively wet spring, which led to high mildew pressure. That was the main challenge of this vintage. Once that was managed by doing our job as winemakers, the conditions were relatively easy. We harvested the whites a little later, and they have much higher acidity levels than in 2022, meaning a lower pH. The whites are more interesting than those of 2022.

As for the reds, they reached perfect maturity without the blockages sometimes encountered in 2022. In Sauternes, we have tanks we might never replicate because the wine is incredible. Botrytization started in late September, fueled by a summer heatwave. We only made two selections. The yield in the appellation is 12.5 hl/ha, which is quite low. We reached 16, but 2023 was an expensive year, with more than a 16% increase in wages and phytosanitary products.

Fortunately, we produced 20% more volume. However, two major concerns remain: producing the wine and selling it. It’s a challenge, especially as we face the brutal effects of climate change. We have to live with it, and there’s a risk that our insurers may no longer want to cover us.

Between 2006 and 2016, I worked with my father, a period during which we didn’t experience major climatic events. Despite a few difficulties in 2013, we managed to maintain a decent yield. In general, for most properties, even if a vintage is criticized by journalists, it eventually sells. But when there’s no production, there’s nothing to sell, unless you have stocks. That’s the big difference compared to the trading side, which can always move lots. The worst for us is not being able to produce due to the extreme violence of weather conditions. It’s a terrifying situation. Since 2017, we’ve faced frost, mildew, black rot, hail, more frost, drought, and in 2023, heavy mildew pressure, although we managed to limit the damage. But at what cost! All these climatic phenomena deeply concern me, especially in a market that isn’t responding. The situation is extremely difficult, and it affects all price ranges.

Terroirs, Vineyards, and Cellars

G: What are the main technical challenges that Bordeaux will face in the coming years?

JJ: We are fortunate here in Bordeaux compared to other regions; we don’t have a water problem. However, adapting to climate change is a reality. We have some leeway to mitigate these effects. Twenty-five years ago, we were leafing Sauvignon vines; today, we no longer do that. In the past, we harvested around September 10, but now it’s earlier, around August 22. Twenty years ago, people said that Petit Verdot wouldn’t ripen in Bordeaux; now we look at it with admiration. Adaptation will have its limits, but for now, we still have considerable leeway.

Of course, wine consumption is declining globally, but I don’t feel that this is the case for fine wine priced between €10 and €35. I believe Bordeaux cannot align itself with industrial viticulture. If you’re going to drink industrial wine, you might as well buy Argentinian wine, for example. It’s much safer, it has flavor, and it’s appealing. Here, viticulture is a craft activity. And craftsmanship is not industry. As soon as we tried to transform craftsmanship into industry in viticulture, at least here in France, it didn’t work. In Argentina, where you pay a tractor driver €300 a month, you can create a wine industry. Here in France, it’s much more difficult.

The challenge is to continue producing excellent quality-to-price ratios and to inspire the world with icons. But these icons must be linked to Bordeaux bottles that everyone can enjoy at home or in restaurants. I don’t think Bordeaux will survive on ultra-premium labels alone.

G: Is there still a future for small châteaux in Bordeaux?

JJ: It all depends on what we call a small Bordeaux, but I don’t believe in a Bordeaux priced at €1.80 at all. I believe more in a good bottle priced between €8 and €10, but unfortunately, that does not reflect the reality of the market. Since Bordeaux wines are not sufficiently valued, it becomes difficult to invest and, consequently, to produce quality. This creates a vicious cycle; if we want to bridge the gap between €1.80 and €10, which is enormous, a profound change in our tools and offerings is necessary.

Unfortunately, this will likely lead to the disappearance of part of our vineyards, a process that is already underway. Currently, 9,000 hectares are subsidized for uprooting, but another phenomenon is occurring in many properties, whether wealthy or less wealthy: production is refocusing on higher-quality plots. As a result, many properties are uprooting 3 to 4 hectares without necessarily replanting. This is a necessary process, but it is crucial that the remaining structures remain economically viable.

Personally, I think Bordeaux will quickly have a total area of 90,000 hectares instead of the current 110,000. This is, for me, part of the solution. I have a great-grandfather who came to the region after World War I. I found a note in a 1960s harvest notebook where he wrote that he already felt there were too many vines in Bordeaux. He wondered if producers and merchants would be able to sell and value the production. Today, we have the answer…There is no example in the world where valuation has occurred without a certain rarity. Bordeaux is the exception. On one hand, we have exceptional valuation; on the other, we have deplorable valuation. Currently, this situation benefits neither side.

The Bordeaux Brand

G: You have traveled the world and its vineyards throughout your career; does Bordeaux still have many assets?

JJ: Today, there is a lot of talk about certification and how wine is produced, but the ultimate goal of each wine is its destination, meaning the taste it provides. In Bordeaux, our wines have a unique taste thanks to our oceanic climate, the 900 mm of rainfall per year, our terroir, and our expertise. Our Médoc Cabernets do not taste the same as a Cabernet from Napa Valley. Bordeaux has a true identity, and its wines are characterized by the terroir, allowing them to stand out. In Sauternes, this uniqueness is even more pronounced because we produce something truly exceptional in a sector where global competition is low.

In addition to this identity asset, we are fortunate to have water. In the new global wine map, it is clear that by 2050, some areas in the south of France, in Europe, and elsewhere in the world will be affected by drought and will no longer be the same. Bordeaux has sustainable viticulture. Irrigation will never be the chosen path because vines do not feed the people. We have an identity taste and sustainability over time. We still possess the expertise, although this expertise is exported and is therefore no longer an exclusive advantage. Another asset of Bordeaux is its geographical location. It’s a beautiful city with easy access. Historically, this is a blessing because it is located near the sea, which allowed us to export our wines centuries ago. This geographical location provides us with a climate that will help us survive despite its upheaval.

G: What positioning do you want for your brand(s)?

JJ: Denis Dubourdieu Domaines encompasses six estates, including two Crus Classés in Barsac, two properties in the Graves, one property in the Côtes de Bordeaux, and Château Chantegril, the third property in Barsac, which is not classified. In total, we have 130 hectares and produce about half a million bottles. We are fortunate to produce three colors: white, which represents half of our production and makes us an exception in Bordeaux. Our roots are in Barsac; our DNA is to produce sweet wines. The other half of our production consists of red wines, which have long been less known and less sought after. Today, with Clos Floridène red or the Hommage à Denis Dubourdieu, 100% Petit Verdot, we are achieving a good level of valuation for our reds and our region, partly thanks to the Place de Bordeaux, often present during the Primeurs campaigns.

My father placed the wines on the Place in 1995. Today, if we are where we are, it is largely thanks to the influence of this organization. I try to position our wines as a safe bet in the distributive category for the most part. However, there is a significant difference between Reynon Blanc at €10 and the Extravagant de Doisy Daëne, around €300 for a half bottle. This is interesting for us because we have an extremely wide range of clients, whether they are merchants or end customers. They all share one common point: stability of quality and price with a family signature. We value this highly, and we are fortunate to be a family proud to put its name on the wines it produces. In my commercial strategy with our merchant partners, I try to ensure that the Dubourdieu story is told through several wines. Overall, we have succeeded in this because very few trading houses buy only one wine from us. This is a small victory because we have never forced anyone to do so, and our wines do not have the same positioning, but they share the same philosophy: the guarantee of seriousness and price stability. We have succeeded in establishing ourselves as a safe bet, even though we are neither speculative nor very well known. However, among knowledgeable or professional clientele, we enjoy a solid reputation.

G: Which of your recent achievements would you like to share with your customers?

JJ: I would like to talk about the cellar at Clos Floridène. This is a long-standing project of my father’s. Until 2017, we vinified Clos Floridène at Château Reynon. With the 2017 harvest, we were able to commission the cellar at Clos Floridène. It was a real challenge to construct 2,000 m² with energy autonomy and to produce fertilizer thanks to a giant composter of 150 m². Here, we vinify Clos Floridène and Château Haura. We also have a guesthouse. For our family, it was important to give a foundation to Clos Floridène and to offer our clients something to see. It is essential to come to the site. The perspective of our partners changes when they visit; everything becomes more tangible. The place is unlike any other. We are in the Graves, but just a stone’s throw from Sauternes, the Ciron, and at the edge of the Landes forest. This unique geological area of limestone is omnipresent. Being able to show our public, our clients, and partners the expression of limestone in the Graves is unique. Here, we make a wine that does not exactly taste like other Graves wines. This has also contributed to the reputation of our white wine. Clos Floridène is one of the few properties in Bordeaux to produce more white than red. This is our badge of honor (38 hectares in total, including 23 of white). We have very old sémillons here, and at Doisy Daëne, we are going to produce a wine that is 100% sémillon. We have already been making 100% sauvignon cuvées since 1948. To celebrate the centenary of the family, we wanted to create a tribute cuvée, which we call 1948, although it is entirely composed of sémillon. Doisy Daëne was the first Cru Classé to produce a dry white, even before Yquem. This confidential production is limited to 1,200 bottles, for which we selected the oldest vines located on the limestone areas of Barsac, the freshest ones. This sémillon has both creaminess and liveliness. The elders used to say that the sauvignons “sémillon.” The two great whites, one 100% sémillon and the other 100% sauvignon, will have a link through their terroir, which will offer consumers an interesting comparison to make.

G: What future projects are you currently working on? (Technical, marketing, or commercial)

JJ: We have a project at Château Doisy Daëne to expand the cellar to vinify Doisy Dubroca as well, a property we purchased in 2014. The land base, with the two Doisy properties, has grown faster than the facilities.

G: Why do you want to keep these two names?

JJ: It was not our initial intention when we acquired Doisy Dubroca in 2014, while my father was still alive. However, we pulled up all the vines from Doisy Dubroca, and the first vintage was produced in 2019. It was so different from Doisy Daëne, even though there is only one row of vines separating the two properties.

Each property has a distinct story, which allows us to offer exclusives to our merchant partners while protecting a classified growth. This consideration led us to keep the name of the Château. Furthermore, the consumption rhythm of sweet wines is different from that of red wines. We have found that segmenting our offer improves sales. It is always more difficult to sell large productions under the same label in Sauternes, especially when competing with well-established brands, as is our case. This strategy allows us to attract a wider range of clients.

The Business

G: What are your priorities in terms of commercial development?

JJ: I’m a great believer in the United States for our distribution and the type of wines we produce. Our wines offer good value for money, and they’re arriving on the American market, which is already highly valued for its domestic production. Our prices are attractive, the quality is impeccable, and the market potential is enormous. There are certainly equivalents in Asia, but not with the same stability over time. The American market is mature and still has a lot of potential, because per capita consumption is very different from that in Europe. Even so, the French and European markets remain unavoidable for us.

My first markets were France and England. In my parents’ generation, it was Belgium, replaced by England and Japan in the 1990s. When I joined my parents at the end of the 2000s, the United States took over and became our leading market, with a very different type of customer. It’s a dynamic market, but one with a lot of uncertainty, not least because of the elections. I also have an old dream for our whites and sweet wines: it’s the African continent. There’s no reason why, in the next 20 years, we shouldn’t find a few countries where they’ll be as popular as champagne. I’m much less focused on China than some of my colleagues. There are some extraordinary markets in Asia, like Japan and Korea, especially the latter which has a fascinating dynamic. We mainly sell En Primeur wines, which account for around 60% of our sales. Despite the current situation, we have good stability with our Primeur customers. Half of our Primeur sales are white wines, which can be delivered quickly, making them more suitable for marketing. We need the Primeur campaign for the visibility and financial support it provides. For independent families like ours, it allows us to remain autonomous. The Primeurs are not just about promoting our image, they’re also about the sustainability of our business model. If this system were to disappear, we’d adapt, but it would be a shame and would mean wasting time and holding back investment and development. We would have to change our business model. That would be a shame, because La Place de Bordeaux is an extraordinary sales force that we don’t always use effectively.

We know the managers, but perhaps not enough about the merchants’ sales teams, who don’t always think about our wines. There’s real work to be done with the La Place sales force. It takes time, but it has to be done. It would be nice to hire someone to do that, but it’s expensive and our wines are very much a family affair. If I find the right person, I’ll have to pass on the family DNA. I’m always afraid of upsetting our partners, the négociants, but we have to do it and push our wines. Our wines aren’t promoted very much. Our partners buy because they have sold them. The tariffs are disappearing fast, which bothers me because our wines will no longer be on offer, resulting in a loss of visibility and therefore sales. It’s an old business rule. It’s something I’d like to improve over time and by recruiting someone, which may happen by chance. It’s an opportunity to meet someone who could help me. The wine trade also has a role to play in telling the story of our wines around the world, as you do with this newsletter.

G: A few words about the opening last December of your wine shop in downtown Bordeaux?

G: A few words about the opening last December of your wine shop in downtown Bordeaux?

JJ: I opened a wine shop in the city center of Bordeaux, the Cave de la Rousselle, in the heart of old Bordeaux. We have 300 references, so it is not identified as Dubourdieu at all. That’s not the point. I opened this shop because I love other wines from Bordeaux; that’s our priority, as well as those from other regions. As a wine merchant, the first thing I did, like any good merchant, was to look at the average margin and the wines that generated the most margin at the end of the month. It’s with Bordeaux wines that you earn the least. Besides being expensive, they tie up capital, and the percentages decrease because you have to round the prices down. It’s not Bordeaux “bashing”; people love Bordeaux. It’s just that the average wine merchant makes the same observation as I do: we don’t make money with Bordeaux wines. This is the limitation of the open system because we cannot control the prices of the wines distributed by La Place. This experience as a wine merchant is very interesting. We sell 8 out of 10 bottles of Bordeaux wines. We have the disadvantage of our strength: extensive distribution is a strength, but with excessive transparency that harms the margin. In the neighborhood wine shop activity, there’s something working in our favor: people no longer have cellars. They buy the bottle for immediate consumption. Our goal is to facilitate access to wine for visitors to the city while creating a tasting club that brings together local residents. At a time when we talk about deconsumption, it’s important to offer access to wine that goes beyond just a promotional offer or an online discount. It’s about creating an authentic and shared experience around wine, fostering a local community, and promoting more thoughtful and quality consumption. By buying from a wine shop, there’s a social and even human act involved. The physical aspect still has a bright future ahead, even for wine.

Favorite bottle of Jean-Jacques

G: If you had just one heart bottle?

G: If you had just one heart bottle?

JJ: It would be the homage to Denis Dubourdieu, made from 100% Petit Verdot, with the first vintage in 2018. This bottle carries a sentimental story with my father. It’s a small cuvée that found immediate success. It was wonderful to have had this idea, to bring it to fruition, and to see such commercial success. It’s always an emotional moment to enjoy it with my mother, my wife, and friends. My mother loves this wine, and it pleases and makes me proud because I also created it for her. We produced 3,000 bottles, with a consumer price of around 35 to 40 euros. The heart of our existence lies within this price range. Then, my wine culture and childhood memories are strongly linked to great sweet wines, particularly the old vintages of Doisy Daene. A Sauternes from another century is unforgettable. No other wine has provided me with as much emotion. When we think about the techniques used to make these wines at that time, it’s fascinating. The winemakers had to rely heavily on their intuition. Today, with the technical means at our disposal, it seems almost unnecessary. We certainly have other problems, but we don’t have more merit than they did. These wines are fascinating. I was lucky enough to taste Château Lafaurie Peyraguey 1895, a bottle that has never left the estate. Nothing has given me as much emotion. This motivated me greatly in my collective action. I am co-president of the Sauternes Barsac appellation. It takes a lot of time, first to bring everyone together at the table, from the owners of the prestigious Château d’Yquem to the small grower with only 3 hectares. This is true in all appellations but even more so in ours. Ultra-luxury coexists with pure craftsmanship. Redefining our specifications has been a priority, and more concretely, we have implemented an authentication process for our used barrels intended for spirits. This is a great success. Groups from all over the world now use the Sauternes name with an authenticated barrel, and the resale price of these barrels has increased from 50 to 500 euros.

All of this allows winemakers who were not used to using barrels to do so and to resell them later because they are almost self-financing. We also have joint projects for the development of wine tourism and for preserving the ecosystem around the Ciron. It’s a patronage effort for which we need to involve public and private stakeholders. It’s exciting to do, and above all, we must move forward together!

Gerda BEZIADE has an incredible passion for wine, and possesses a perfect knowledge of Bordeaux acquired within prestigious wine merchants for 25 years. Gerda joins Roland Coiffe & Associés in order to bring you, through “Inside La PLACE” more information about the estate we sell.